Those in power were fiercely opposing this through intimidation and with outright violence. South Africa in the 1970s was a country moving towards change. Probably doing something she shouldn’t be” You said she’s a young lady, this Black? She probably ran off with someone, what d’you expect. “And then the officer said, be grateful we keep you safe in your house, meneer, don’t worry about the other people.

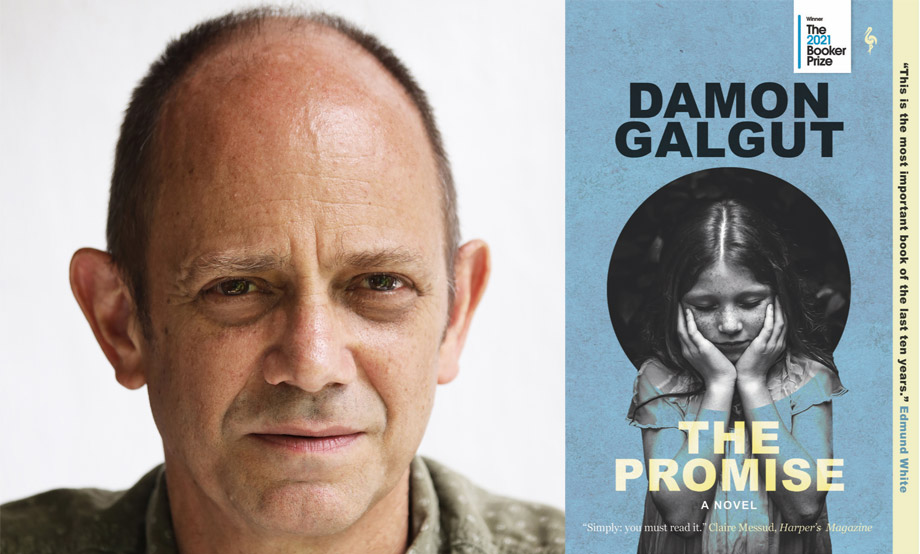

View The Good Doctor on Goodreads For another short, intense literary novel, take a look at my review of Hot Milk by Deborah Levy.This review was written for and first published by Berfrois. The world at the end has irrevocably changed, but it is for the reader to decide how. This novel has my favourite kind of ending, neither too tightly tied up, nor hanging unresolved. You must decipher images, snatches of dialogue, gestures, the arrangement of a room. You experience the world anew, without assumptions, preconceptions or easy explanations. While it dissects the cruel absurdities of oppression and corruption, the word apartheid doesn’t appear once. The Good Doctor doesn’t preach or explain. Like the greatest prose, the magic somehow rests in the space between the words. It is astonishing but you don’t quite know how it’s done. Galgut’s writing is brilliant: terse, fierce, like being jabbed in the chest relentlessly. It takes you into a world that is uniquely its own, a dark, claustrophobic place where nothing is certain or familiar, where you are constantly stumbling for sense, where the emotions are vivid but the facts are contingent. Frank’s voice is so intense that any more would be too much. The Good Doctor is the perfect short novel. But there are complex social and political forces in play, and his actions have terrible consequences. Laurence is young, idealistic, determined to shake things up. Some staff see salvation in moving on, others wallow in resignation. The hospital was opened under apartheid, in what was deemed a homeland (impoverished parts of the country that were set aside by the regime for illusory ‘self-determination’).Īpartheid has gone, but their hospital somehow remains, poorly resourced, its staff all waiting for something to happen, the few serious cases they encounter transferred out. His world is upturned when an idealistic young Laurence Waters is posted to work with him. Frank Eloff is a world-weary doctor in a remote South African hospital.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)